I think it’s fair to say not all Greeks like rebetiko, but it remains central to Greek musical identity, even in an age that is drowning in pop music. Rebetiko heavily influenced the laiko music that defined Greek popular music through the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s, and the music – and the rebetes’ romanticized approach to life – influenced Greek folk and rock music, even as the early-century music was being rediscovered and heard again.

It’s not surprising then that many musicians of the last half-century have explored the rebetiko repertoire, absorbing the songs even as they performed them in interesting ways. I want to highlight a couple or three videos that capture this.

Let’s go for the leek (wallet), Ourania Lampropoulou (santouri) & Evgenios Boulgaris (oud & voice)

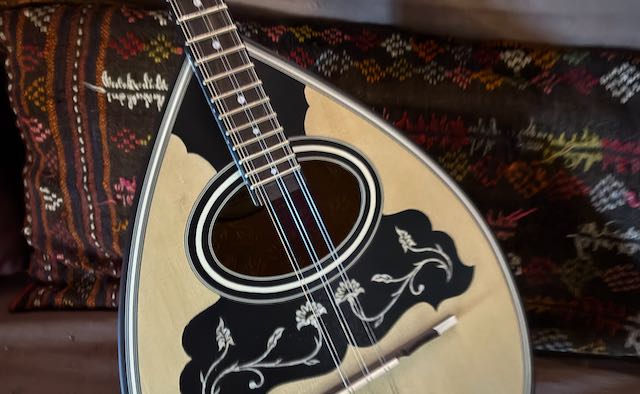

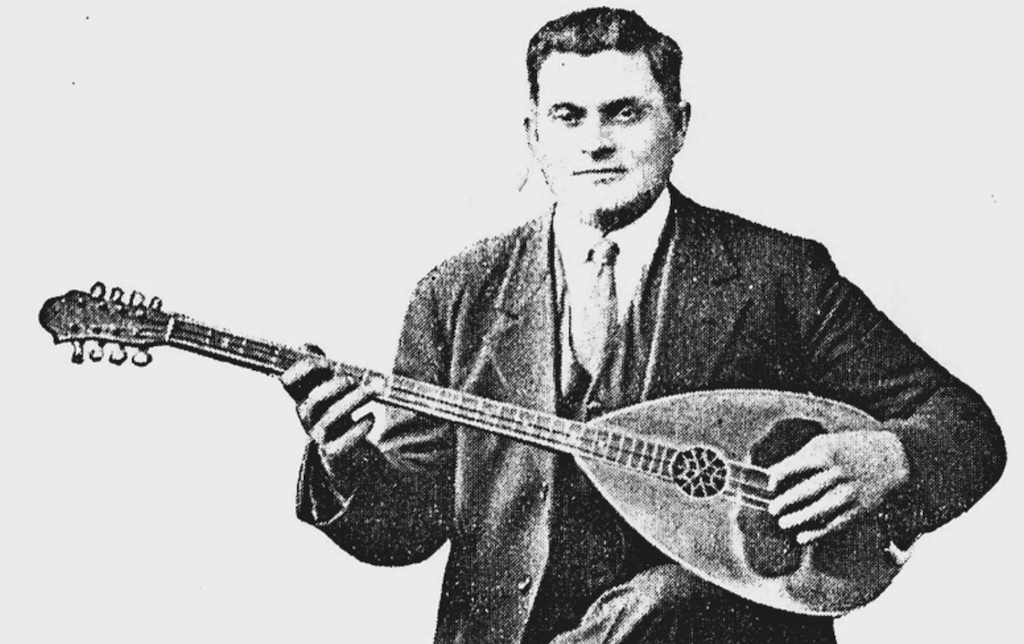

This song – odd title and all – is old rebetiko treated faithfully, using instruments that were essential to Smyrneika-style rebetiko but that weren’t heard in Greece for decades.

First though, that title.

Thanks to my partner for finding these: online sources suggest the Greek word πράσο is rebetiko-related slang for wallet, as well as being the (non-slang) word for leek. So the song appears to be a call to go to the market, beat someone up and take their wallet.

The original of the song, recorded in 1934 by Rita Abatzi, featured violin and oud, and versions I’ve come across have incorporated guitar, bouzouki, cumbus (a metallic sounding Turkish stringed instrument) and santouri, but this is the only YouTube version I’m aware of with just santouri and oud. Compared to the original, the feeling is that it is faster and more urgent. Other versions are truer to the original or, in some cases, a little slinkier and more laid-back.

Ourania Lampropoulou is the sister of Sofia Lampropoulou, a kanun player who ranges well past the traditional Asia Minor music most associated with the kanun. The sisters, who have performed and recorded together, are well-known of exploring a wide range of music beyond traditional Greek folk. Here, her exuberant, driving playing provides a wall of sound that propels the song along relentlessly.

Evgenios Boulgaris is one of a handful of musicians who have delved deep into the rebetiko repertoire, and the musical development and theory behind it. He has published at least one book that combines theory and transcripts of more than 200 rebetiko songs from the pre-WWII era. A multi-instrumentalist (oud, bouzouki, a bowed instrument called the tanbur and others) and singer, he is known for not only lovingly recording the old songs, but his skill in developing and playing taxims – improvisational passages that set the mood and tone of the song. (I’ve taken at least four online seminar classes with Evgenios: He’s a great teacher and a really, really nice guy.)

My Hookah, Imam Baildi & Eisvoleas

My Hookah is based on the 1935 recording Hookah, Why Do You Go Out, by Georgia Mittaki, which was typical bouzouki-guitar rebetiko. Imam Baildi, an Athens-based group that borrowed its name from a Turkish stuffed eggplant dish, has taken it and – as with so many of their songs, both original and reimagined – added horns, rock influences, some rap, a little touch of Latin music and more. The original song is still there but – as the crowd from this 2012 concert shows – it’s entertaining new generations.

Adding outside influences to rebetiko is not new. As well as the well-known influence of Asia Minor music, early rebetiko musicians incorporated Italian cantata into love songs. As rebetiko moved further into the mainstream, it adopted sounds from Latin and Arabic music, and especially Indian film music. There are even a couple of late ’50s, early ’60s songs that combined rebetiko with early rock and roll.

Imam Baildi drinks from that creative stream, taking old rebetiko and adding layers of sounds to create something fresh that appeals to new generations and, in the process, exposes them to some good, old music.

George Dalaras, Drunk and Stoned

When it comes to reinterpreting rebetiko, we can’t overlook the recordings that George Dalaras did in the 1980s and beyond. They are as responsible as anything for rebetiko becoming more popular and entering the mainstream of Greek popular music.

If Kazantzidis was the voice of Greek music beginning in the 1950s, Dalaras was the voice of Greek music through the late years of the 20th century and into the 21st. During his career – which is still going – he has recorded almost 90 albums (which have sold more than 18 million copies worldwide) and contributed to more than 150 others. From his Wikipedia page: “His first memories of music were the basic forms of Greek music, such as traditional, folk, rebetiko, laïka, which influenced him as an artist. In addition, he has performed many other music genres in several different languages, such as pop, rock, latin, contemporary, byzantine music, classical, opera etc. He has collaborated with many Greek and foreign artists (composers, poets, maestros, musicians, etc).”

(His father was also a well-respected musician, Lukas Daralas. George swapped a couple of letters in the last name.)

Dalaras made rebetiko much more respectable than it had been. He combined his polished, warm and expressive voice with extensive orchestration, appearing on stage with dozens of musicians and singers – including sometimes full orchestras. The result was lush music that appealed to those who found the early recordings harsh and even unmusical. (You can compare this performance with Anestis Delias’s original as an example.)

The fact that so many Greeks can sing along (often loudly and lustily) with so many songs that are now almost a century old is in large part due, I suspect, to the efforts of Dalaras and those who followed him to make them easy to listen to and accessible. And that’s no small thing.

Leave a Reply