Just as the line between rebetiko and the laiko that followed it are (very) blurry, so is the line between rebetiko and folk music.

In fact, many of the rebetiko pioneers of the 1930s used the terms rebetiko and folk music almost interchangeably, as did laiko composers of the 1950s and ’60s. Some of those composers, like Dimitris Gogos, wrote tunes that have been fully incorporated into the field of Greek folk music. And rebetiko musicians in the 1930s were not above recording the odd village dance or two.

And many of the early recordings that were to become integral parts of the rebetiko repertoire, were pieces attributed as παραδοσιακό – traditional.

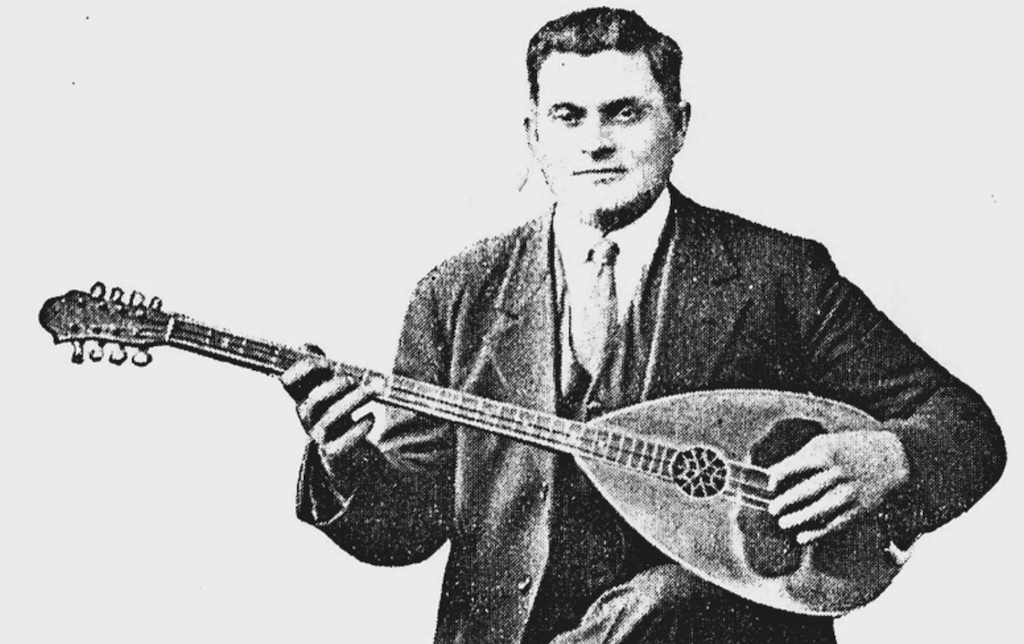

One of those was The children in your neighbourhood, credited as a traditional song from Asia Minor when first recorded in 1925 in New York by Marika Papagkika. It was subsequently recorded in Athens by Antonis Diamantidis (Dalgas) and others as it passed firmly into Smyrneikan rebetiko.

Since then it seems like it has never NOT been recorded, with almost every major Greek recording artist of the past 20 or 30 years taking a shot at it. It was included on George Dalaras’s influential album 50 Years of Rebetiko Song. Giannis Haroulis, the wonderful Cretan singer who regularly sells out concerts throughout Greece, is on video singing it, while an arena full of his fans singing along. It’s been played with rock influences and pop touches, and it’s been played for folk dancers. It may have come to be known from the early 20th century rebetiko scene, but it keeps crossing boundaries.

The tune itself is as simple as folk song, but it’s lyrically rebetiko, too. The singer complains that the children in the neighbourhood (of a lover? a friend?) abuse him when he shows up drunk, falling down and crawling in the mud. Memorably: “All ouzo, ouzo, ouzo, I’m tired of it / Bring me a little cognac.” Maybe something a little more sophisticated will help him overcome all that ouzo from the taverna.

(Rebetiko has seemingly dozens of songs that mention ouzo. That may be worth a post some day.)

I’m going with the Dalgas version from 1930, which more clearly than the peppier and more polished versions that came later captures the pathos of the song and hints more strongly at its roots in music from Asia Minor.

Leave a Reply