Think Greece. White and blue buildings. Sandy beaches. Bouzouki music. Salads topped with with slabs of feta.

And ouzo. Not just a potent potable, but a potent symbol of Greece. Anise-flavoured, distilled, and, since 2016, decreed by the EU as a Protected Designation of Origin, meaning only Greece and Cyprus can produce and sell ouzo.

Ouzo is also a potent metaphor, especially in early rebetiko, for everything from the desire to forget life to an empowering agent. Ouzo is present, at least in passing, in dozens of songs and, is central in more.

We’ve already seen how ouzo is responsible for the downfall of the narrator of The children in your neighbourhood.

Earlier, in 1929, Kostas Nouras explored similar territory in All the ouzo.

All ouzo, ouzo, ouzo, ouzo, I’m sick of it

…

Let’s have a beer I’m sick of it

…

Your neighborhood kids are teasing me

You drunkard, you drunkard, you bum, they call me

…

I’m gonna get them and beat them up

Not a happy guy, nor a happy song. It’s either a slice of someone’s life, recounted in song, or a cautionary tale about all that ouzo and what it does to guy. The kids are wise to it: the man’s a drunk. And they know they can tease him because while he wants to beat them up, the chances this drunkard is going to catch them are slim.

The same year, Antonis Diamantidis (Dalgas) recorded the simply titled Ouzo, with a different story about the spirit.

Everybody calls me ouzo, the girls admire me, oh my

And on the street they tease me

Come on, you ouzo man, I’ll make you an ouzo party,

Bring us some santouris and fiddles, oh, my, oh, my

That takes us from ouzo as the source of a downfall to ouzo as source of fun, excitement and parties. The girls can’t have a party without santouris and fiddles and – of course – a little ouzo to lift the spirits and keep the party going.

When I drink it, I take my time, don’t empty the bottle, oh dear…

…the narrator sings near the end of the song. Ouzo is for sipping, for keeping the spirits high and sustaining the party. None of this falling down and wallowing in the mud.

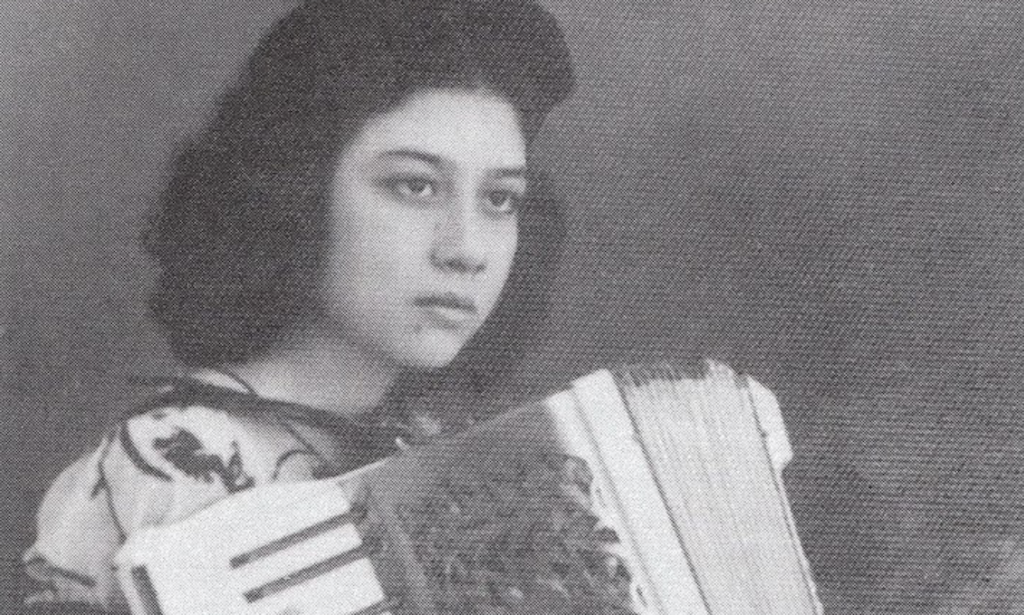

A few years later, Roza Eskanezi is lamenting what ouzo won’t do, in the much-covered song Ouzo and hashish.

Morphine ouzo and hashish, oh my, oh my

I try to forget

But I couldn’t do it, poor thing

I’m about to lose it

…

You’re in love with someone else, oh, my.

What do you want with me?

Not a penny, you little bastard

I don’t have a penny for you.

We know ouzo is potent (it has to be 40 per cent alcohol by volume, and is usually between 40 and 55 ABV). Those who’ve indulged can attest to the potency of hashish (which was then legal throughout much of the eastern Mediterranean) and morphine (which contributed to the downfall and even death of some rebetiko musicians, such as Anestis Delias). But even that combination isn’t enough to overcome the raging heartbreak of a woman scorned.

This is ouzo as a powerful aid to trying to forget, something that Kostas Roukounas addressed in Ouzo, ouzo the same year.

Ouzo, ouzo, ouzo, ouzo bring, carafes ah, to cover pains, bitterness and illnesses.

In ouzo to drown them, to forget everything.

Ouzo, ouzo ouzo, no matter how much ouzo I drink I can’t, ah, I can’t drown them.

(The song is mid-tempo and sounds surprisingly upbeat. I have theory that the sadder the lyrics of a Greek song, the peppier it will be. There’s something about that juxtaposition, I suspect.)

All those pains and bitterness have learned to swim, he sings, and fly to the top of the ouzo. There are sorrows that cannot be drowned. We’re never sure of the cause of the pain, but we know people are laughing at him for the ouzo he’s drinking, which is probably adding to the pain.

If we jump forward 40 years, in the immediate aftermath of the rebetiko revival, we’ll still find ouzo this time, in Haris Alexiou’s Ouzo when you drink.

From evening till morning my life is my own,

and I conquer the whole world, I sip a fine ouzo.

…

When you drink ouzo, you’re straight

King Dictator God and Almighty King

And if you drink it, you’ll be happy

And you’ll see everything in the world is rosy!

The undercurrent is that others may see Greece as wounded, poor and distressed, there is nothing that a little ouzo won’t cure. It becomes a symbol of Greekness, a way to “conquer the world” a sip at a time. It may make you drunk, but it makes you a little defiant, too. That’s potent.

(An alternative read is that ouzo will show you everything in the world is rosy, even when it is not. Both of those strains are present in the Greek spirit as far as I can see, so you get to choose your interpretation.)

That’s only a sampling of songs, but it pretty much shows the range of how songwriters and performers saw the power of ouzo, for good and bad. Much like whisky in the annals of country and blues music, ouzo played a prime role for Greek musicians who explored the angels and devils of our better natures, if I may be allowed to wax a little poetic.