Classic era rebetiko is sometimes “romanticized as manges, outlaws, hash dens and alluring females,” (the quote is from Dafni Tragaki, author of Rebetiko Worlds).

It’s also, to a large extent, a musical world of relating stories about love in all it’s aspects – head-over-heels love, unrequited love, jealous love, lost love, painful love, secret love, forbidden love… The emphasis seems to be on the painful aspects of love – the wounded heart, the unheard sighs, the shattered nights – which may not be surprising given the storytelling pontential.

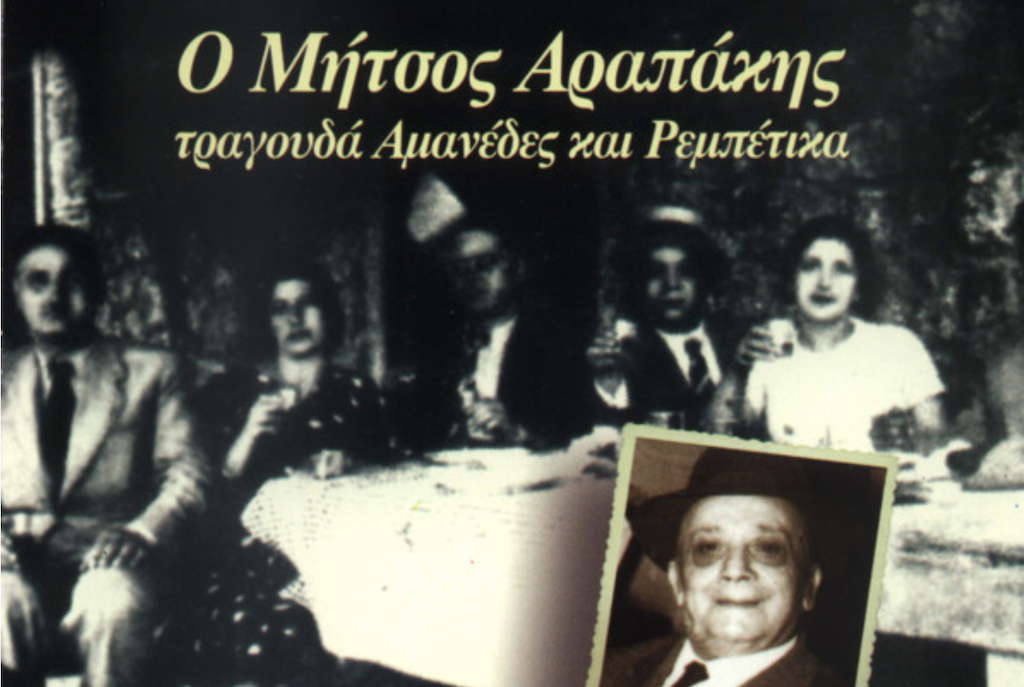

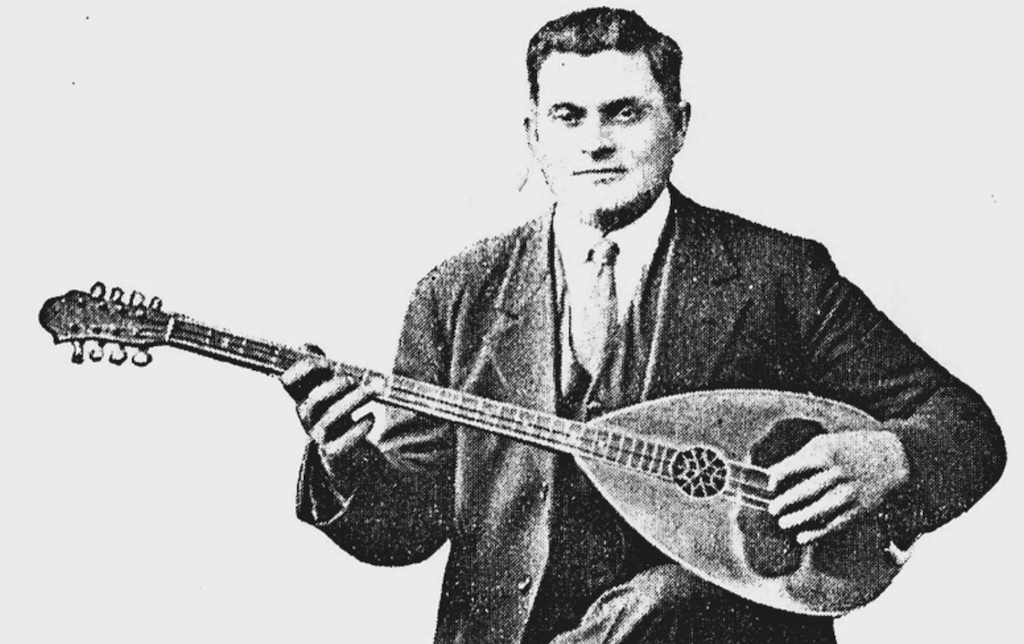

I’m not here with the definitive word on rebetiko and love, but I can tell you that in translating lyrics and toting up numbers, love seemed to be a pretty big deal to Markos Vamvakaris.

I took a look at the Mississippi Records release Death is Bitter, “continuing Mississippi’s exploration of the darkest reaches of Greek music,” a compilation of early Vamvakaris pieces. There are 12 cuts, two of them instrumentals. Of the remaining 10, six are songs about the attractions of woman or love. Only three are about drinking and smoking, or criminal activity, in the night.

In a couple of sheet music compilations of Markos’s music that I own, the split is at least same: in one, seven of the 14 pieces relate to women or love (three of those seven express admiration about women with dark eyes). In the second one, there are 19 pieces transcribed. Twelve of them are about women and love.

(Compilations are tricky things, though. What’s included is up to the compiler and they don’t often give reasons for what they have chosen. In the case of the sheet music books, one seems to be based on Vamvakaris’s best-known pieces, and the other on songs that illustrate musical modes in the pre-WWII years.)

Delving into Vamvakaris’s entire output of songs would take considerable time. I have no way of knowing for sure, but I suspect that if I put that time in I would find as many love songs as songs of the rebetes. Maybe more, in fact, because the Metaxas censorship rules took away a lot of other topics.

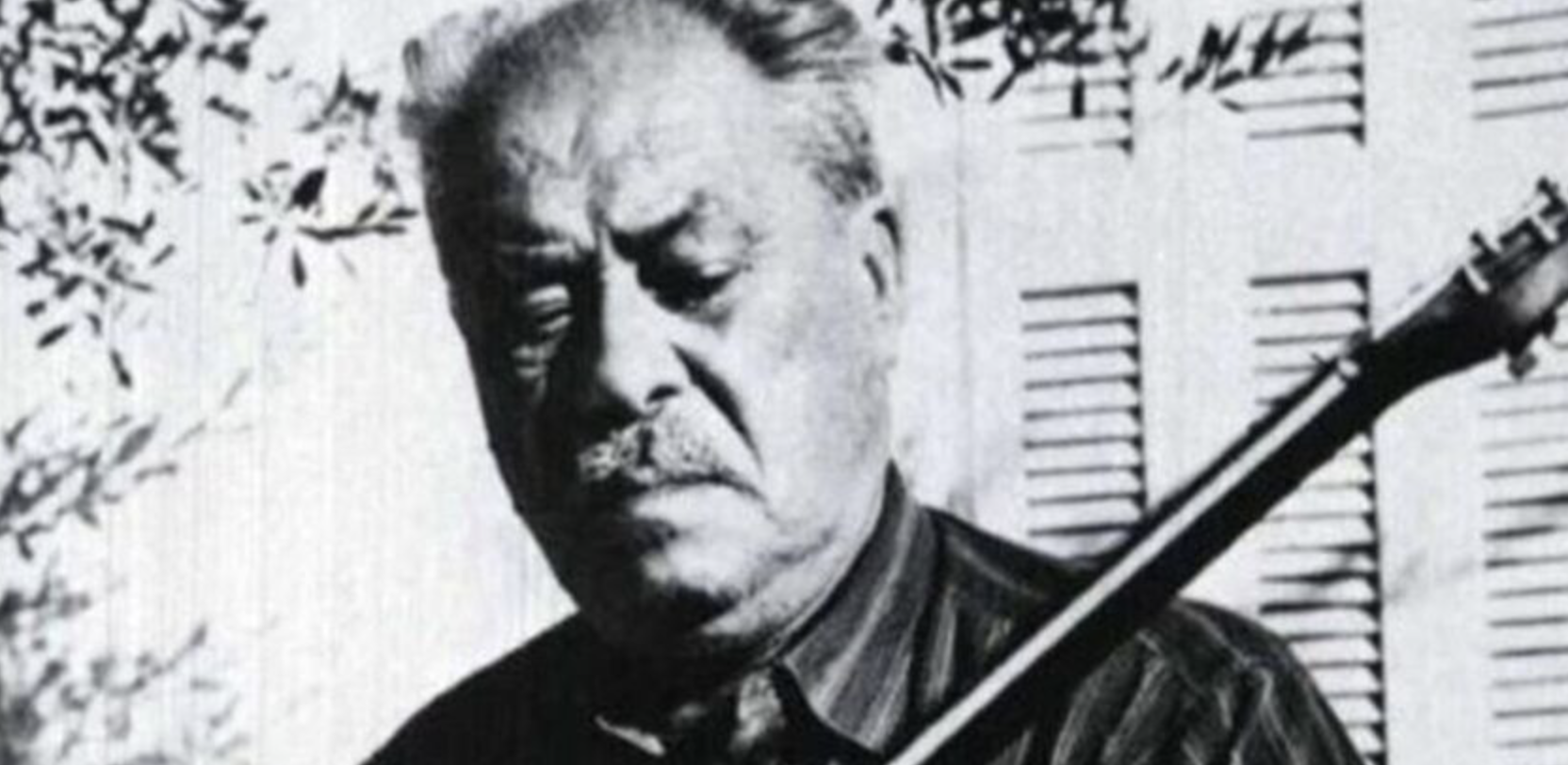

The reasons are pretty simple, I think. One is that, as he made clear in his autobiography, Markos Vamvakaris loved women (not always sequentially).

The other is that Vamvakaris and others wrote their rebetiko classics from life, and what is more central to life than love? What is more central to live than the attraction to another, sometimes forbidden and sometimes unavailable? What is more central to life than the joys and pain that love carries with it? What is more central than the daydreams hatched by the glimpse of dark eyes?

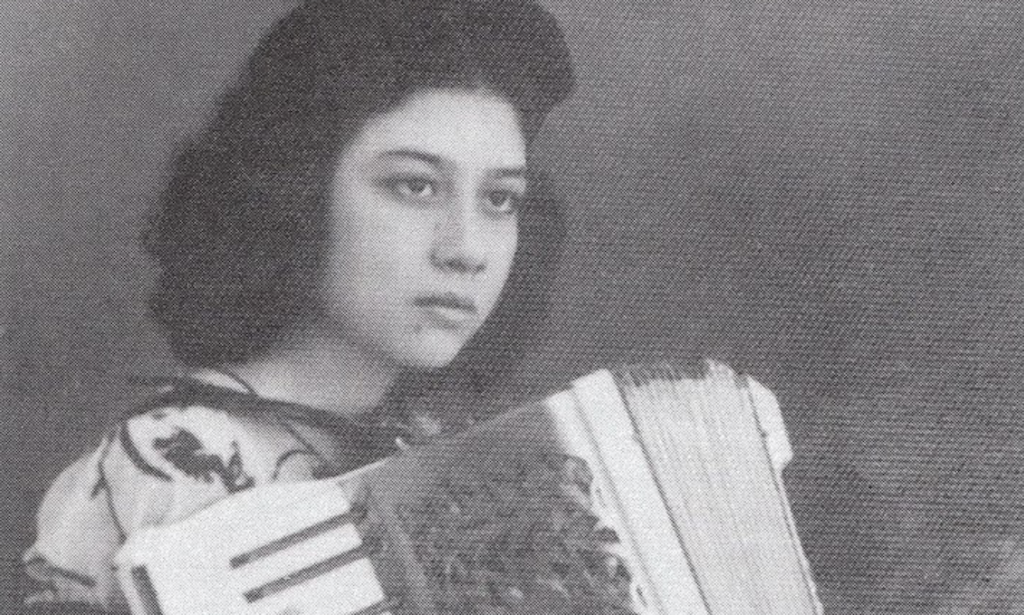

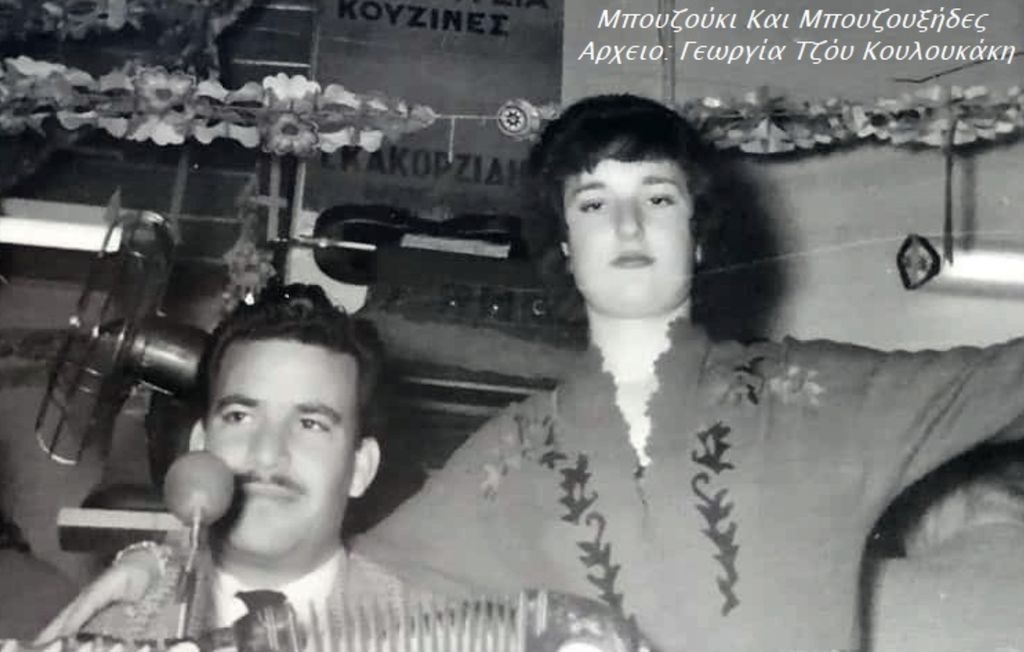

So, for Valentine’s Day, a love song: They told me not to love you, written by Vamvakaris and sung by Nota Kalelli. The final verse:

But let the world say whatever it wants

I will love you

to the ends of the earth if you said so

and if you wanted me to I will go

Leave a Reply