Rebetiko re-releases and compilation albums tend to concentrate on singers and composers – rightfully so – but instrumental music also played an important role in rebetiko, particularly in the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s.

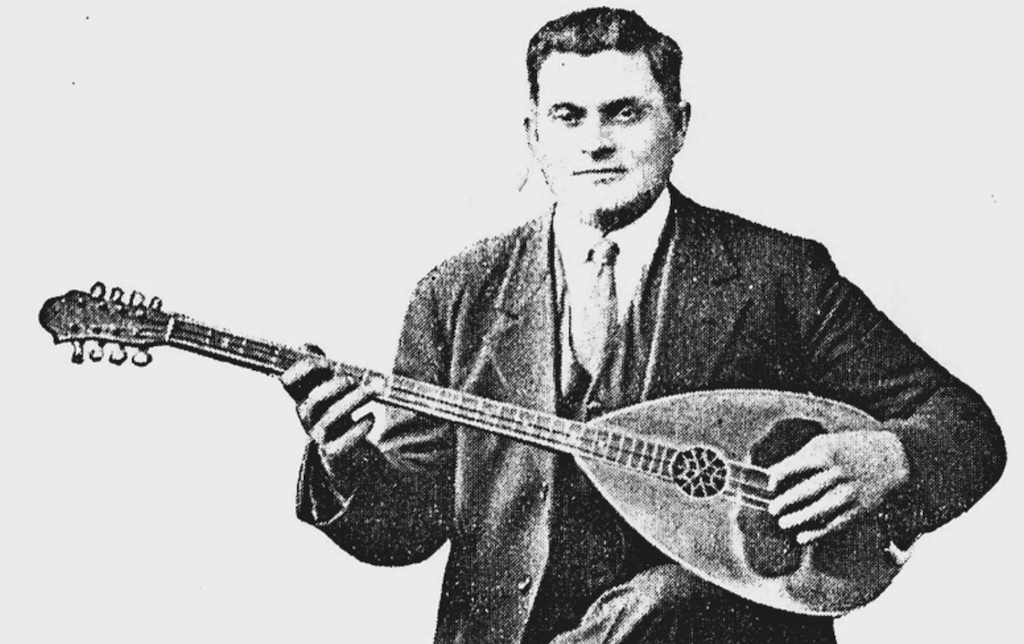

In fact, one of the recordings credited with playing a huge role in the development of the bouzouki-driven Piraeus style were the instrumentals To minore tou teke and the B-side Misterio zeibekiko, recorded in the U.S. by Jack Gregory (Ioannis Chalikias) in the early 1930s. They not only inspired musicians, they help create a demand for recorded bouzouki in Greece.

Markos Vamvakaris, noted for his gruff singing style and the vitality of his often simple lyrics, recorded a number of instrumentals that are still prominent in the rebetiko repertoire: among them Arap zeibekiko in 1933 and Taxim zeibekiko in 1937, which features a wonderful, long introductory taxim.

Vamvakaris’s band-mates in the Famous Quartet of Piraeus, Giorgos Batis (baglama) and Anestis Delias (bouzouki), recorded Athens and zeibekiko taxim in 1937, and in the same year, Fragiskos Zouridakis (also known as Stavros Tzouras) recorded Syriano hasapiko.

It’s actually hard to find a bouzouki player who didn’t record an instrumental and while they are not as well-known as the sung pieces, there is some marvellous music there. Vasilis Tsitsanis has a number of instrumental pieces in his discography, the best-known of which is probably Ta Oraia tou Tsitsani, a fast-paced showcase of his bouzouki-playing skill. Yiannis Papaioannou’s 1954 recording of Guzel taxim is masterful. Apostolos Hatzichristos recorded the spritely Servikos dance in 1940.

Those are only a handful of the music-only pieces that formed a key component of rebetiko, whether it was to play songs for dancing (primarily zeibeiko and hasapiko), to show off playing skill, or just to bring something different to the bandstand and give the singer a break. (Given that musicians would often play through the night to the hours just before dawn, a break would have been appreciated.)

A lot of the instrumentals recorded after the mid-1950s through the 1960s and into the 1970s are not to my liking. By then, the bouzouki was often over-amplified and drenched in reverb, and the songs focussed more on flash and speed than on the musical content. Some of these pieces – often instrumental versions of older rebetiko songs – made up the contents of hundreds of cassette tapes and CDs that promised “the sound of Greece,” but delivered a pallid version of rebetiko. Anyone who has walked through Plaka and been aurally assaulted by multiple versions of Zorba or the theme from Never on a Sunday can attest to that. Fortunately, there are still a handful of profession a musicians and dozens of amateurs playing in Greece that love the older sounds and can bring them to life with skill and finesse.

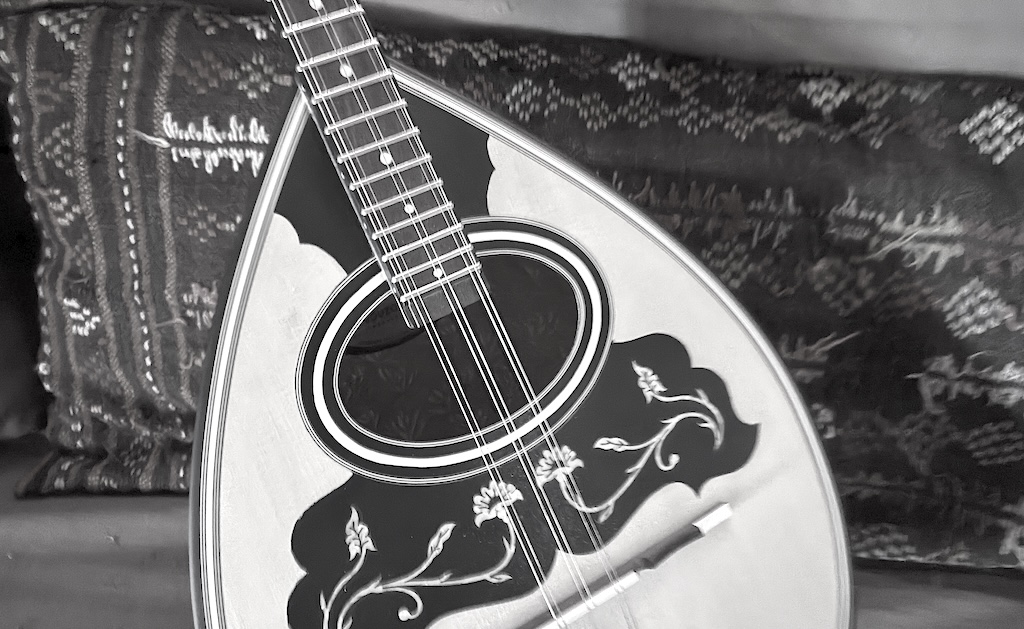

I’ll leave you with one more, a Vamvakaris piece that I am (slowly) learning on bouzouki. Don’t make me stubborn is a lively hasapiko recorded in 1938.

Leave a Reply