This blog is partly about sharing a genre of music I love; it’s also, in no small part, about my own exploration of and education about rebetiko.

Eleftherios, or Lefteris, Menemenlis is a recent discovery, whose recorded works provide an aural bridge between the world of Smyrna and Athens, and the link between the popular music produced in Asia Minor and the rebetiko that came of age on the Greek mainland.

Greek Discography credits him with more than 130 recordings, starting in about 1907 and ending in the late 1920s. Many of the recordings were made in Smyrna before the Catastrophe, and more were made in Athens after. Among them are some of the classic pieces that have come to identify Smyrneika rebetiko and that are still part of the rebetiko ensemble.

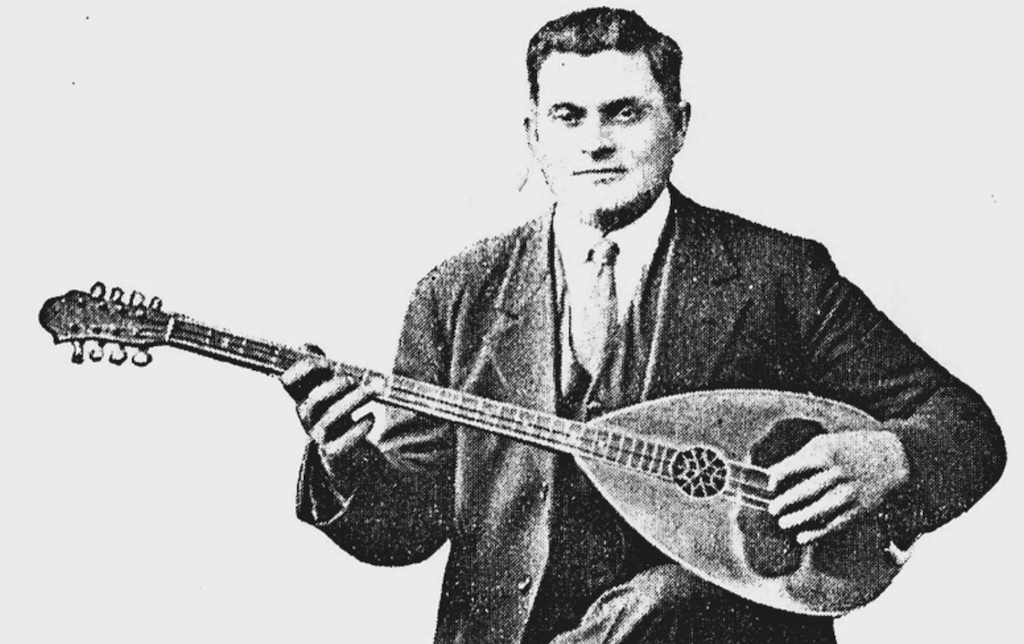

Menemenlis was born in 1874 as Eleftherios Beslemedakis in Menemeni in Asia Minor, near Smyrna. (Hence his rechristening with the last name Menemenlis.) He played guitar and was a singer, credited with being one of the first to sing amanades. He recorded a wide range of styles in Smyrna, including folk, rebetiko and Turkish songs, but especially amandes, recording 28 of them.

His career continued when he arrived in Greece, where he was among the group of musicians, singers and composers from Smyrna who were helping create the classic recorded music of the 1930s. He recorded in Athens for the first time in 1924 for Odeon Germany, which recorded many of the early rebetiko songs before the launch of the Athenian recording studios.

YouTube has many of his recordings, the last of which seems to have been made in 1927, when he was 53.

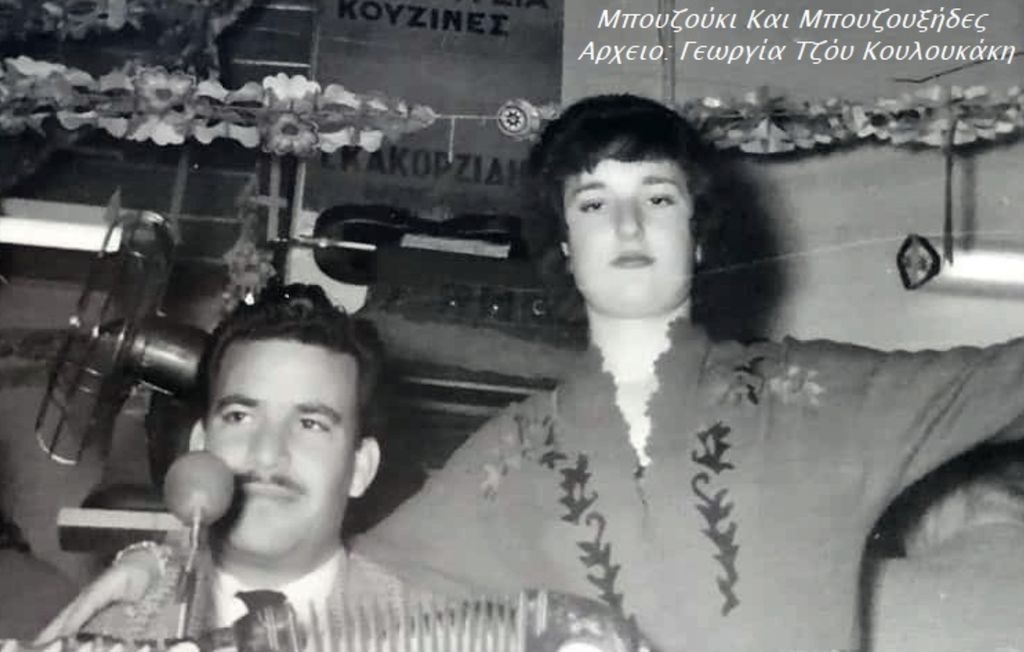

You don’t tell me where the hash is sold was one of the songs recorded in 1927 – he seemed particularly busy in 1926 and 1927, if the discography is correct. I’m including two videos here. The first is the original from Menemenlis, which features his strong tenor voice backed by santouri and violin. The second is a live performance from six years ago that features singer Dimitris Mistakidis, a very fine guitarist, here playing the bouzouki. It shows how the old songs can be remade – the flowing sound of the original replaced by a driving rhythm and almost defiant singing – while retaining the rebetiko feel.

Leave a Reply